|

| Caerleon, Wales -- a Roman amphitheater |

|

| Ogmore-by-the-Sea, Wales -- a 12th century castle |

An Agent and Her List Discuss Children's Books, Publishing and Beyond

|

| Caerleon, Wales -- a Roman amphitheater |

|

| Ogmore-by-the-Sea, Wales -- a 12th century castle |

|

| (Now you're really wanting to test the clouds-slowing-your-fall theory, aren't you?) |

|

| Beautiful, no? I'm kind of in love with my mountains. |

I spent my second semester at VCFA

weeding out old technology, resurrecting a sick grandma, and mining for the

heart of the story. The only things that didn’t change were the basic characters. (Well, except for Gram—she got a make-over and a new lease on

life.) I revised the manuscript for fourth semester as my creative thesis, and

Sara sold it later that year.

I spent my second semester at VCFA

weeding out old technology, resurrecting a sick grandma, and mining for the

heart of the story. The only things that didn’t change were the basic characters. (Well, except for Gram—she got a make-over and a new lease on

life.) I revised the manuscript for fourth semester as my creative thesis, and

Sara sold it later that year.  |

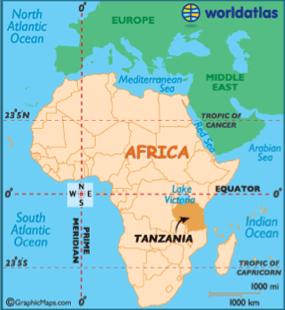

| Tanzania's there in dark orange--just below the equator. |

|

| Me pounding rice. Yes, I know the glasses look a little silly--it was the 1990s. |

|

| Modesta in 1999. |

|

| A picture of Modesta a friend gave me on the day I left Tanzania. |

|

| One of the many hard-working girls I met in Tanzania. |

|

| Nyerere in his home village. |

|

| Me and Modesta in India--note the glasses upgrade. |

TAKEN was one of those stories.

TAKEN was one of those stories. |

| An imaginary pigeon therapist? Oh really? |

|

| Yawp! |

1) Interactivity works. There are times when you stand up in front of a classroom or auditorium and think: Uh oh. The students might be staring at you glassy eyed and zoned out. They might be looking at everything except you and fidgeting with enough chaotic energy to power a small city. They might, occasionally, be glaring at you with expressions shifting between distrust and outright hostility. I've found one thing that works in all of those cases: Asking them questions.

I try to involve the students early and often in my presentations. I am dyslexic and spent a second year in second grade, rereading the same few Dick & Jane books over and over again. Instead of explaining what a Dick & Jane book is, I ask if anyone knows. Interestingly, many of them do. The same goes for Dungeons & Dragons (the first books I read independently). As a bonus, the kids' definitions of both are often pretty funny.

In general, instead of giving examples, I like to ask for them. Instead of telling a story, I like to ask for volunteers to help me create one. The transformation can be remarkable, from a few half-raised hands at the start to a roomful of kids pumping their hands upwards as if they’re trying to touch the ceiling.

2) Embarrass yourself!

Another great icebreaker is humor. Specifically, humor at my expense. I like to show one of my old school photos near the start of the presentation. It lets them know that I don’t take myself too seriously and never have been able to dress myself. In addition to getting them laughing, it levels the power dynamic a little and makes them more comfortable talking to me.

3) PowerPoint is your friend. I shied away from using any sort of AV component in my early school visits. I had visions of technical difficulties dancing in my head and was concerned that technology would create a barrier between me and the audience. I was wrong about that. So very wrong.

Using PowerPoint, or a similar program, to illustrate your talk allows you to do more than just project mortifying middle school pictures of yourself in comically large proportions. It adds another element to your presentation and, just as important, gives it structure. Clicking onto the next image, watching the little video, whatever it is, it allows you to reset things, to proceed neatly and sequentially to the next point. It provides a framework that the students grasp immediately.

It's also unobtrusive. I used to pass around old Super Bowl press passes from my sportswriting days. I thought it would be fun: Show and Tell! Instead, it was a distraction. Kids were handing them the wrong way, looking over each other’s shoulders, grabbing. Now I show a picture of me standing next to an NFL player, and then a Sports Illustrated Kids cover story I wrote. They look at it, get the point, and we move on. The sports fans think it’s cool; the others aren’t unduly bored.

From a technical perspective, I bring my own laptop and adapters, and every school I’ve been to so far—from inner cities to small towns—has been able to provide the rest.

4) Memorize it! It really, really helps if you memorize your presentation. (The PowerPoint pictures are great helpers/placeholders.) In fact, you should have it memorized well enough that you can make adjustments on the fly without losing your place.

I learned this lesson back when I did standup comedy, and it is the same with school visits (though, thankfully, without a two-drink minimum). If students see you reading, they will tune out. It’s amazing how quickly it happens. I carry a printout with me (or leave it on the podium, if I’m using one), in case I lose my place. As soon as I look down at it—within seconds!—I hear kids start to fidget and sometimes whisper. I can hear myself losing them! As important as it is to engage them early, it is just as important to keep them engaged.

The picture above is from a visit to Arlington, VA. Note: There's a dinosaur on the screen and no paper in my hand. Also, note that there are several hands up and I haven't asked a question. They were just waiting for the next one.

5) They are awesome! School visits used to make me nervous beforehand and leave me exhausted afterward. That is because I was doing them wrong. My visits were loosely structured, semi-memorized, and a bit chaotic. They consisted too much of me talking, too little of me listening, and didn’t have nearly enough funny pictures. Now they are more entertaining and informative for the students (and for me), and I can do three in a day without anyone yelling “Clear!” and slapping electrified paddles to my chest.

Obviously, every author is going to have his or her own style and approach. But these are the things that have worked for me. Involving the students, keeping their attention, knowing what the heck I’m going to say next and having some interesting way to illustrate the point . . . That’s what I learned in middle school last year.